A new experience or career sometimes begins with an unsuspecting wander down Broad Lane in Sheffield. It’s how a few of our current team found their way to Ernest Wright – and Elliott is the latest.

“I commute into Sheffield most days from my family home in Barnsley, for my aerospace engineering studies at the University,” says Elliott.

“I was walking past Ernest Wright’s workshop one day last summer, and you could hear the grinding and general workshop noise.”

“I thought that’s interesting, so I went home and did some research, and I was just blown away by the authenticity of the manufacturing process and conditions.”

A flying start

We were only too happy to take on Elliott, who soon took wing at Ernest Wright, using his mechanical talents to maintain and improve our machinery.

“I’ve kind of picked up where Tony left off on maintenance, and I’m currently restoring one of the ‘Viotto’s [a half-century-old Italian grinding machine] from scratch – hopefully it’ll be running this summer,” he says.

“I’ve also been doing some little tasks like fitting regulators for the air hoses on the pressurised air system, and I repaired the big grindstones because they were all vibrating. If something doesn’t look quite right, I’ll go and sort it out.”

This all seems to have come naturally to Elliott, who previously had only dabbled in mechanical maintenance.

“I ride mountain bikes, so I maintain my own bike, but picking up skills like working on the hydraulic system of a Viotto is totally new to me – so I’ve spent a lot of late nights googling manuals,” he says.

The buds of change

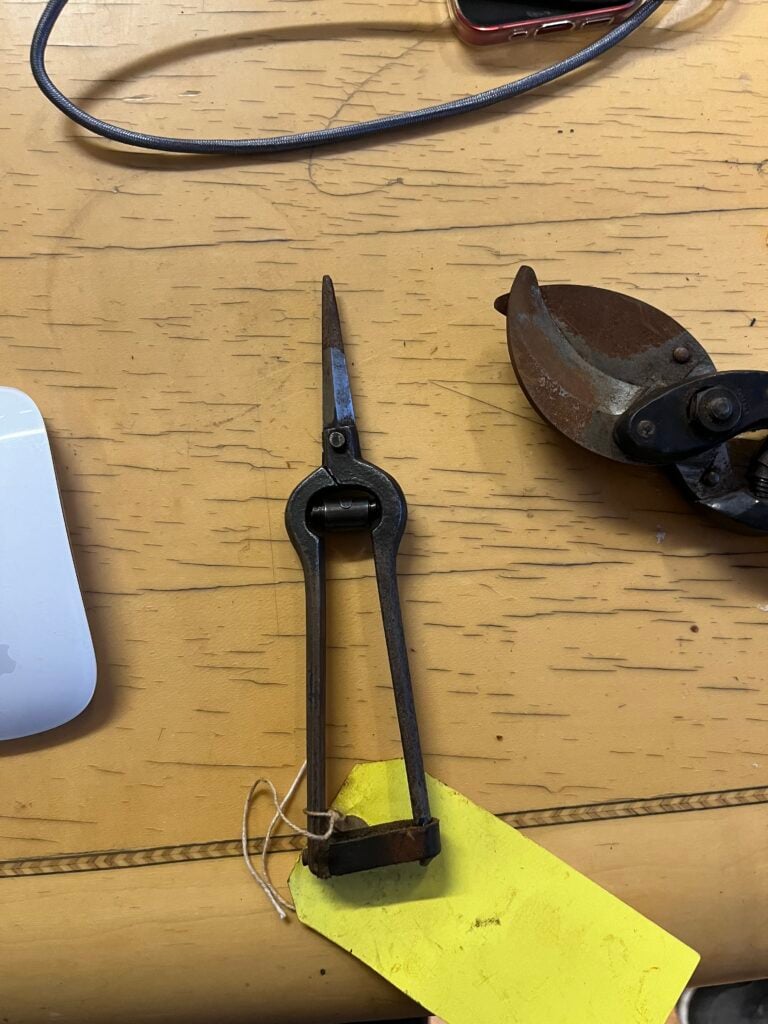

Elliott’s arrival at Ernest Wright has coincided with another exciting development: a project to add a pattern of rose pruners, also known as ‘Nurseryman Scissors’, to our range.

It is a pattern from the early 1950s. We found the last example in the basement of another Sheffield heritage firm, Footprint Tools. However, a lot of work was needed to reverse engineer and adapt the pattern, create new dies, tools and forgings, and ultimately bring the scissors to life as a hand-crafted product. We were at a decision point with redesigning the pattern – and that’s when Elliott stepped up.

“I was busy number-stamping Kutrites, while Neil and Paul were talking about something,” Elliott recalls.

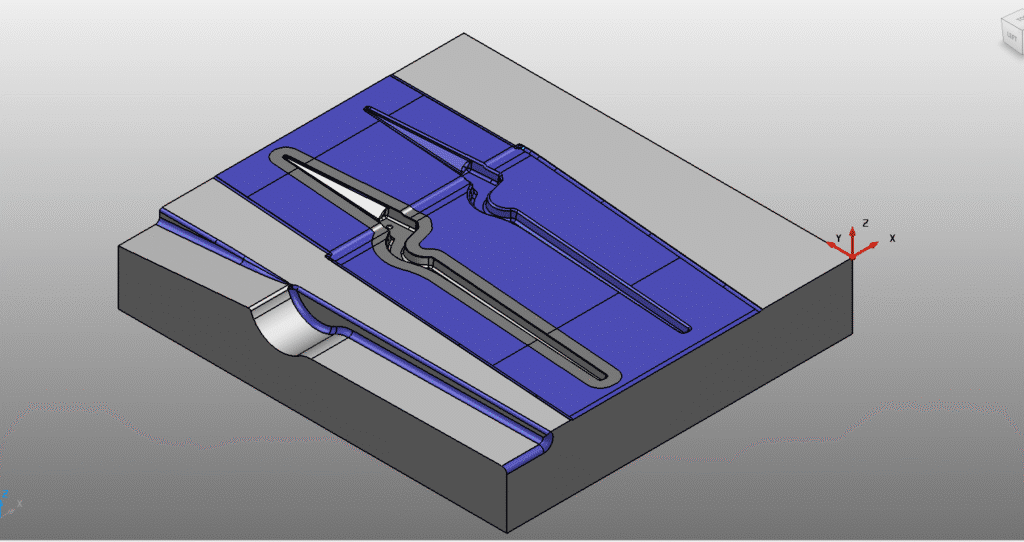

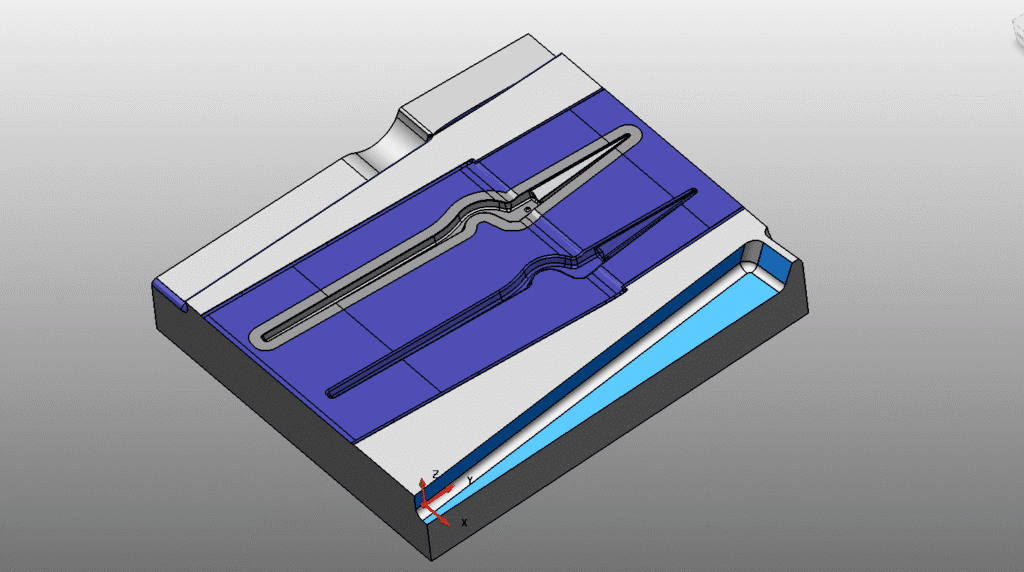

“Neil looked up and asked me: are you familiar with CAD/CAM? And so we went into the office and he started telling me about the new Nurseryman Scissors project, internally known by the project name ‘Secateurs’.

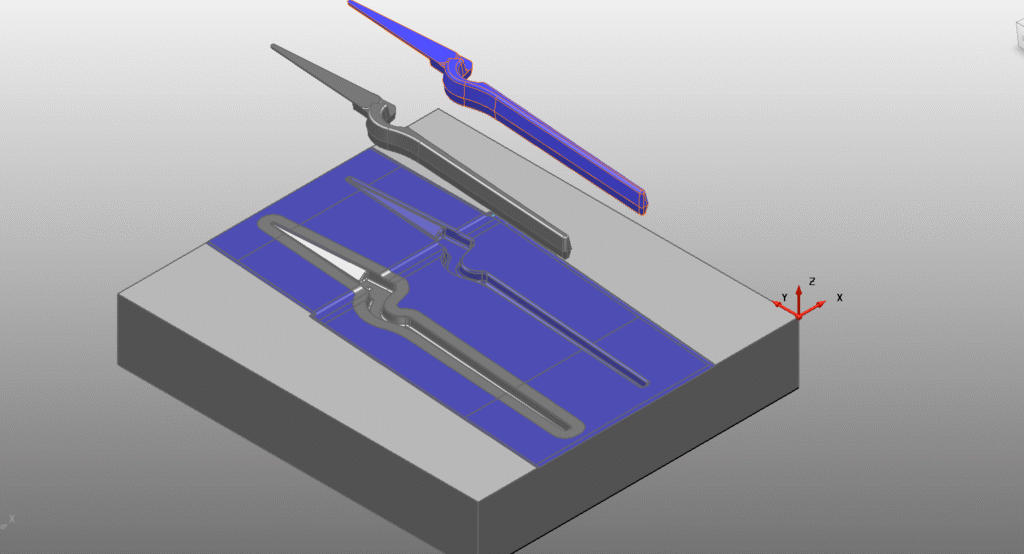

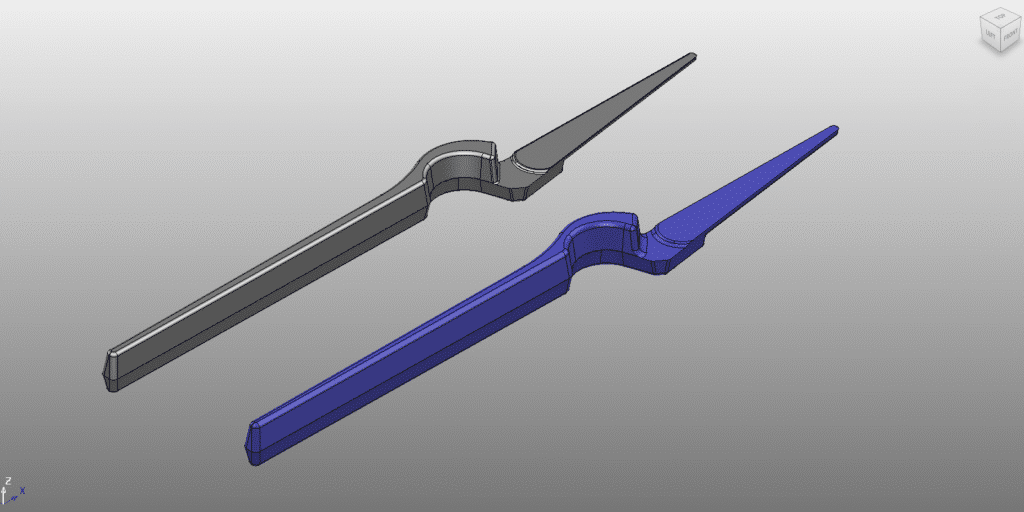

Elliott spent a few days tweaking the pattern’s CAD file – a 3D model of the object – and 3D printed some parts in plastic using his 3D printer at home. The prototype didn’t feel quite right.

“Plastic 3D printing is great for rapid prototyping, but you just don’t get the feel you would with a metal part,” says Elliott.

“We had got to the stage where we were kind of happy with the design, but we wanted to see what an actual metal product would look like.”

An alliance is forged

The last time Elliott had visited the Royce Centre R&D hub at the University of Sheffield, he had been working on a project to create a carbon fibre drone. But with a spark of lateral thinking, he realised the facility could help solve our prototype problem.

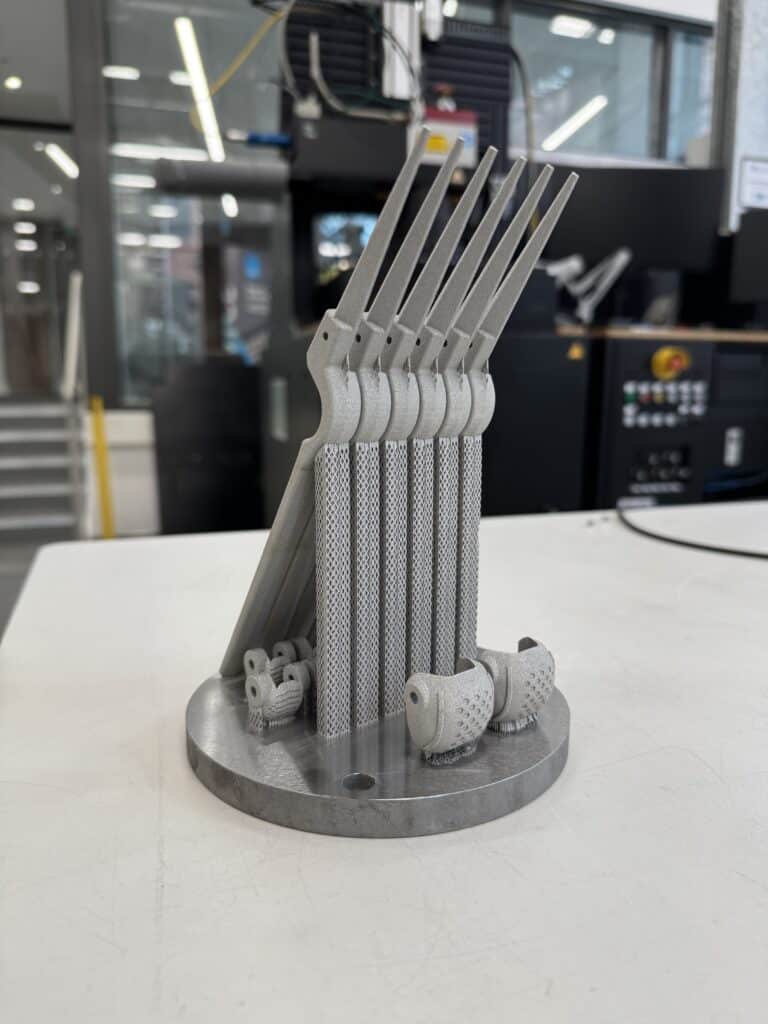

“I had it in the back of my mind that they had metal 3D printers, so I took the original vintage rose pruners to show Milo at the Royce Centre,” says Elliott.

“He said it would be possible to make a metal prototype, so I emailed George, the Centre’s 3D printing technician, and the rest is history.

“We’ve got two sets of printed secateurs, each with slightly different designs, and we’re now happy with the pattern. It’s on its way to the manufacturer of the forging dies and clipping tooling.”

One of Elliott’s requests of the Royce Centre was for the whole Ernest Wright team to visit the facility, and the putters were amazed with the possibilities.

“They had a table laid out with all the different pieces that they printed, including parts that were interlocked together – some of them were forming a gecko figure which had little limbs and body segments,” he says.

“It’s something you’d never be able to do with any normal manufacturing process, and the team were just totally loving it.”

High tech meets traditional

Bringing beautiful vintage tool patterns into the world is a labour of love. The rewards are extraordinary – but the process can be all-consuming. Thanks to Elliott and the Royce Centre team, we now have a way to iterate new patterns that gives us more control, improves efficiency and ultimately broadens our horizons. We suppose that’s what aerospace engineers are for!

The design iteration process might be high tech, but the Nurseryman Scissors will be crafted through our usual, traditional methods. Practising these techniques on the metal prototypes has been a learning curve.

“It’s hard to explain the experience of getting these prototypes and seeing an actual, metal printed part, because it looks like a normal metal part but all the properties are different,” says Elliott.

“When Sam and Neil were hammering away, practising the curves for the pattern like they would with hot drop forgings, the prototype would bend in a totally different way. You can really tell it’s a totally different material.”

Still, the metal prototypes have proven invaluable to our preparations for the recreation of the new (but old!) pattern. We can look and feel how the end product will feel in the hand of our customers, we have a good understanding of the open-close mechanism, and we’ve been able to plan how the pattern will be ground and put together.

“It’s been such a huge honour to be part of this process, with this company that has such a deep history,” Elliott says.

“This will be the first pair of Nurseryman Scissors, pruners or secateurs made from scratch in Sheffield, hot drop forged in Sheffield, and put together in Sheffield in a long time. My dad already wants a pair for his allotment up the road.”