Story, beauty, impact: some of the first things the eye sees when it drinks in the work of Martijn J. Kramp.

It could be a costume made for the Dutch Nationale Opera & Ballet, the suiting worn by Daniel Craig and Drew Starkey in the 2024 film Queer, or a bespoke piece made for a private client under the Martinus Johannes label.

You’ll see the depth to these pieces when you study them closely: the bold, intentional silhouettes; rich textures that encapsulate a time or mood; a standard of finishing to rival that of the most exacting suitmakers. Artful design and masterful tailoring have knitted together under the same gaze.

The shape of things to come

Kramp joined the Dutch Nationale’s costume department in 2008, as a recent audiovisual design graduate of the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam. He had no knowledge of men’s tailoring.

“I simply went there with the idea of, okay, I’ll do this for one year and see how it works, because I wanted to be a costume designer,” he says.

“It put me in contact with the world of tailoring at a very high level, and somehow I got stuck there. I really loved the work of building costumes, and I was lucky to have a great head of department who is a very good tailor.”

Kramp spent the next decade learning the craft under his mentor’s wing, first as a trainee and later as a cutter.

“He showed me all types of technical constructions, all the different periods of costume, and he made me aware of what’s possible with simple construction,” says Kramp.

“I learned that simplicity is a strength – it allows a costume to be very sculptural in its shaping, but still with a certain ease to it.”

The colours on the palette

Now a fully fledged costume designer at the Dutch Nationale, as well as a freelancer working across stage, screen and private commissions, Kramp is internationally renowned for his extraordinary costumes.

“They always start with an idea,” says Kramp.

“Some directors give me an image, an artwork or another inspiration, while others work from the text, the script or the character.”

“From that point on, I start developing my own ideas visually, and I usually create mood boards with images, textures, materials, colours or paintings.”

Mood is one side to the picture – another is research into the historic context of the production.

“I need to learn about the time when the work was written or composed,” says Kramp.

“What were the social conditions back then, and what is the background of the screenwriter or composer?

“I collect materials and images from every source of inspiration, and I curate visual worlds for the director.”

Echoes across mediums

Kramp’s costumes are undoubtedly works of art – and like many great artworks, they can reference other artists from different spheres. We were drawn to the Kandinsky-inspired costumery for a production of Doctor Atomic, John Adams’ contemporary opera about the world’s first atom bomb test.

“The director wanted to start with realism, then make it more surreal scene by scene, through the arc of the opera,” says Kramp.

“It ends with a triadic ballet, which was very typical of the time depicted, and Kandinsky was one of the inspirations for the costumes.”

As the story progresses and the atom finally splits, the world encapsulated in Kramp’s costumes is deconstructed and reordered. Art imitates life.

Constructing the extraordinary

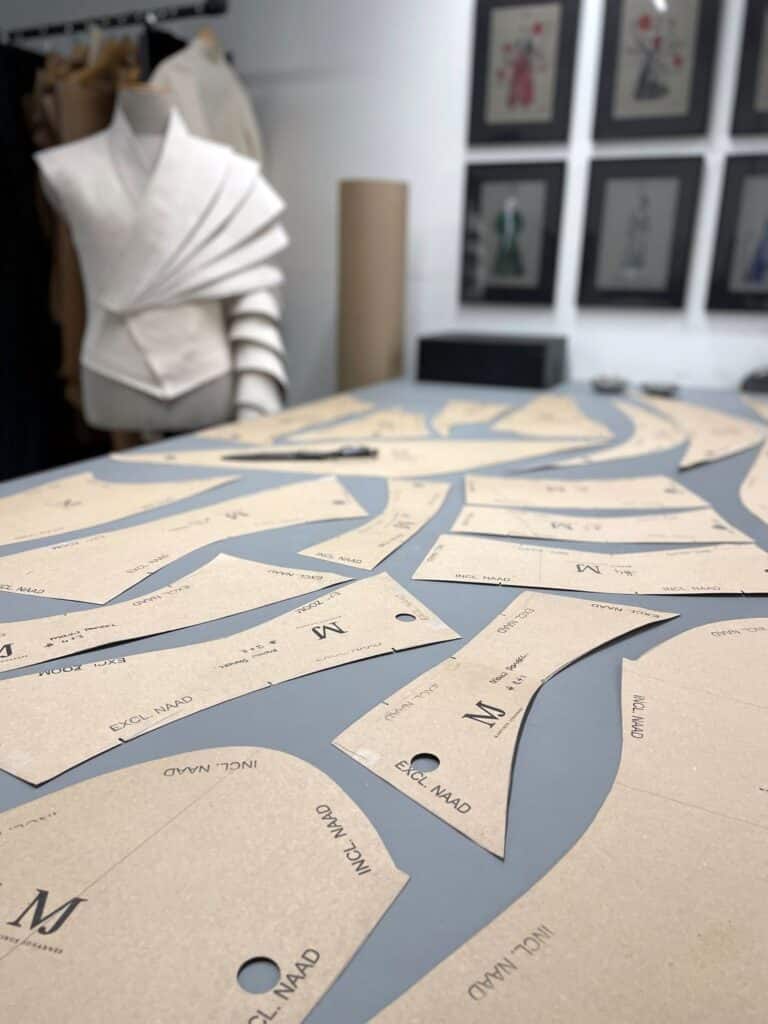

From entire costumes built around geometric silhouettes or layers of sculptural elements, to one-of-a-kind jackets with exaggerated collars, cuffs and lapels, it’s clear that many of Kramp’s pieces cannot be made from an existing pattern. Their singular design must be underpinned by bespoke construction.

“It doesn’t matter what kind of costume I’m making or how crazy the idea is, I always approach it from the technical point of view of being the traditional tailor,” Kramp says.

“After all, I started as a tailor in the opera world.”

Kramp often starts by drafting patterns for the garments, but this approach has limitations. The two-dimensional patterns must follow strict technical rules, and they can come unstuck when translated into a voluminous 3-D object.

“In these cases, I sometimes skip the entire pattern stage and I start working on the mannequin itself,” says Kramp.

“I can arrive at the silhouette, the shape or the layers of the costume, and then I have to translate it back to paper in order to make the construction workable and the process repeatable.”

Moving visions

Kramp must also consider the client’s specific requirements – especially if they’re a performer who needs to sing, dance or blend together costume and character.

“I always think about what they will have to do in the costume, and how many performances are going to be done,” he says.

Private customers, who commission bespoke garments for their own use from Kramp, receive the same level of consideration.

“It requires a balance between exaggerating certain details, and not making the piece too flamboyant or too extravagant,” says Kramp.

“My good luck as a designer for the theatre and privateware is that somehow, I know how to do this in a subtle way.”

The next dimension

“I’m always very minimal in the detailing because shape is so important to me, so I need texture to make a costume come alive,” says Kramp.

“It’s the extra dimension in costume design. The fabric works with the lighting and it gives you the opportunity to add depth to the character and the world around them.”

As well as outfitting the performer, Kramp’s costumes can interact with the setting.

“I sometimes choose to use the same colour or the same texture as the set to make the costume more invisible, which makes it an extra tool to use with an interesting staging,” he says.

The craft behind the costume

It would seem natural enough for a designer like Kramp to talk cerebrally about their work. His pieces are controlled explosions of fabric – loud ones or quieter ones – which express stories, personalities and feelings using shape, colour and texture.

But when you speak to Kramp, you’ll find that he views his work more simply. Perhaps we’re just seeing the outer edges of a tailoring career that made a more spectacular blast than most. He still sees himself as a craftsman, above all.

“Even when I’m designing, I’m already thinking about the construction process, and sometimes I really need to work on the construction part first to have an idea about what I’m going to do,” says Kramp.

“I started as a tailor, and that’s what I’ll always be.”