Crafts connect us to the past, but the hand that swings the hammer or places the stone is right here, right now.

Britain is still a land rich in living crafts, as cultural scholar, Dr James Fox, discovered when he set out to research Craftland: A Journey Through Britain’s Lost Arts and Vanishing Trades (released September 2025, pub. The Bodley Head), his new book on the country’s endangered crafts.

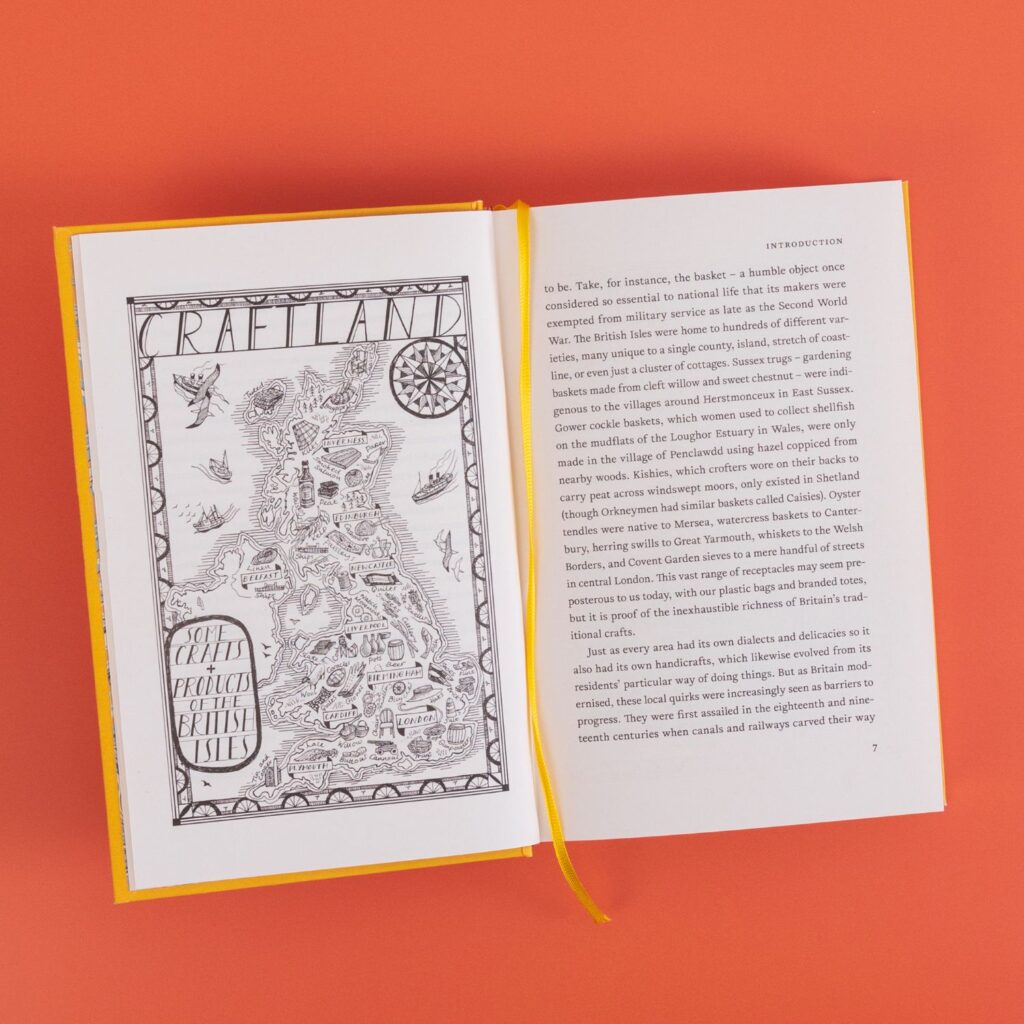

“It’s a record of a journey around the British Isles, from the rural and ancient – starting with seeing dry stone walls in the north and woodland crafts in the Chilterns – through to the urban and the modern,” says Fox.

“I visited the country’s last bell founder in Loughborough, letter cutters in Cambridge, Highland thatchers in Scotland, Jewish scribes, watchmakers on the Isle of Man and West African instrument makers.”

Wherever Fox travelled, he encountered historic crafts (some more ancient than others) which have only survived thanks to the efforts of their few remaining practitioners.

“In Bedfordshire, I met Felicity Irons, who is one of the only rush weavers in the country, having brought the craft back from nothing,” he says.

“When the last rush merchant in the region died in the 1990s that seemed to be the end of this ancient craft, but she bought his tools and punts and taught herself how to do it.”

The 21st century craftsperson

If British crafts are diverse (dozens are covered in Craftland), the people who pursue them are more varied still.

“Some of them are actually very anti-craft, like the wheelwright I met in Devon who doesn’t like to be called a craftsman,” says Fox.

“He thinks of craft as a hobbyist’s pursuit, and speaks of himself as a tradesman because he feels that ‘craft’ is belittling to the idea of having to run a proper business.”

Whatever craftspeople may call themselves, they must have some common motivations to ply their trade. Judging by Fox’s conversations, very few are in it for the money.

“Only one or two of the craftspeople I’ve met are earning a lot, and the majority are just hanging in there, or even living hand to mouth,” says Fox.

“They’re motivated by different things, like the determination to do a good job, to work with their hands or to continue a family business or local tradition. They all are obviously very passionate about their work, even though it might be hard or stressful, and they have a very strong sense of history and heritage.”

It’s the way you work

What is craft? This is a harder question than it might seem: the term overlaps with others like ‘art’, ‘metalworking’ and ‘manufacturing’, and there are strong, contrasting opinions on the definition.

“We’re accustomed to thinking of craft as traditional – you whittle something from wood, toil over a forge, or lay a hedge in the fields – but actually, I think craft is a way of interacting with the world, and a way of being that can be applied to many modern contexts,” says Fox.

“My view is that there’s a craft in many, many modern trades, from screenwriting to graphic design, floristry to bike repair. All are rooted in the idea of thinking through things and completing them in physical space. It’s the way you work, rather than the specific product.”

While working on Craftland, Fox realised that his own act of writing had much in common with the crafts he was documenting.

“Writing often feels to me like hard, manual labour. Okay, I’m sitting in my tracksuit bottoms at my kitchen table, but it does feel like heavy lifting,” he says.

“For me, the closest comparison was with dry stone wallers. They’re trying to put one stone on top of another and then moving it around, and it doesn’t quite fit, so they take it down and find another one.

“I think you can apply the idea of craft as a verb: a way of working in all kinds of activities.”

The trade was them, and they were the trade

Craftland has too much to tell us about the present to be classed as a history book, but it does have a lot to say about the history of British crafts – including many which are now considered extinct.

“We have to be honest that the vast majority of crafts have already gone; hundreds, if not thousands have disappeared over the centuries,” says Fox.

“The majority of them have gone since the middle of the 19th century because of industrialisation, urbanisation, global markets and global competition, and because of changing social and cultural aspirations.”

Fox’s research uncovered a plethora of vanished trades such as back-end girl, badger, baller, beetle cutter, belly man, bender, biscuit and bogeyman, to name a choice few.

“It’s fascinating to go through the censuses and look at the trade names and job titles that were then common, but don’t mean anything to us today,” he says.

“For a long time, the craftsperson’s practice and their identity were the same thing, which is why we have so many surnames that refer to occupations, like Cooper, Taylor or Chandler.

“These people were doing the trade that their father had done and their ancestors had done before them. The trade was them, and they were the trade.”

Crafting the future

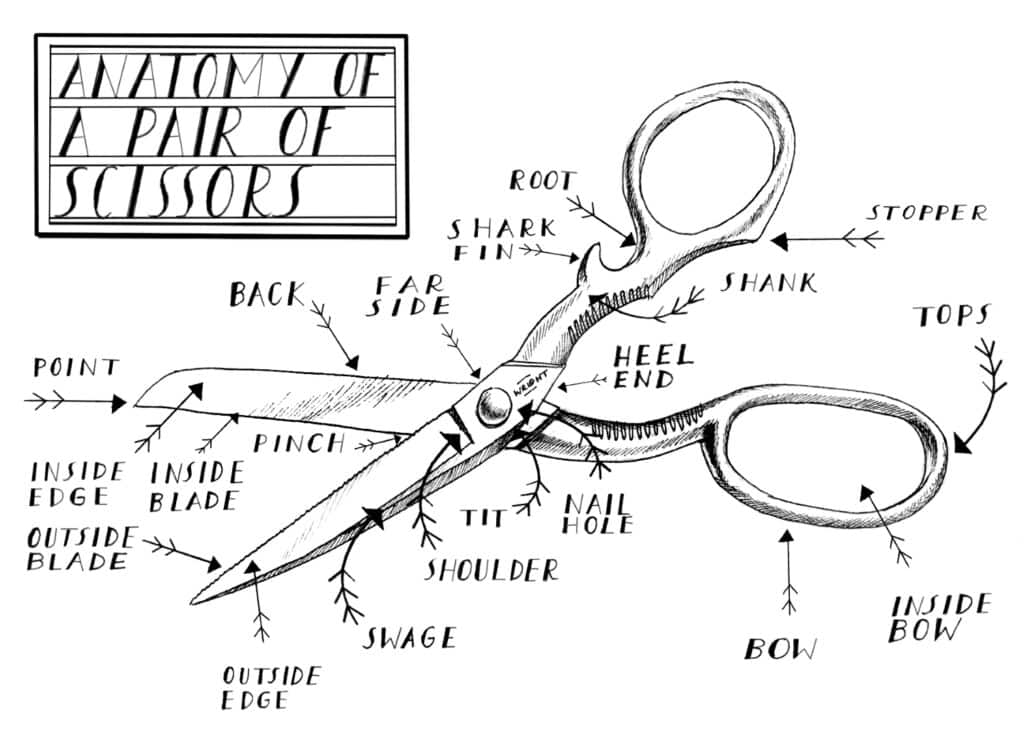

Heritage Crafts lists over 70 crafts as critically endangered in the UK, from arrowsmithing to scissors-making. Are we all doomed to go the way of the badgers and the biscuits? Fox hopes not.

“Craft is a very feasible model for the future,” he says, to our relief.

“As we try to move to a circular economy that’s more sustainable, it tallies quite nicely to focus on crafts which generally use more sustainable materials and practices to produce objects that would be reused for many years.

“They also offer a future for people who are struggling with the cost of living – such as young people who can’t afford to have a flat in London, but can afford a workspace in more rural or less glamorous parts of the country, and who can work in flexible ways which are suited to the modern labour market.

“By extension, craft can inject economic activity, a younger generation and creative practice into communities around the country.”

Where craft met industry

We were honoured to welcome Fox to our scissors-making workshop during his research for Craftland.

“One of the things I found fascinating is that Sheffield is a place where craft and industry worked hand in glove,” he says.

“You had one of the great industrial cities of the world making steel to build the Brooklyn Bridge, the Sydney Opera House, NASA spacecraft and the infrastructure of the British Empire, yet its industrial ecosystem was built out of individual craftspeople, self-employed people like little mesters who were doing their own thing in their own workshops.

“We tend to think of large, collective endeavours as being like lots of cogs working together, but in Sheffield it seems to have been lots of thinking people.”

You can read Fox’s reflections on his visit to Ernest Wright in a chapter of Craftland that’s devoted to Sheffield, Britain’s ‘Steel City’.

“What so impressed me was the enormous effort and investment that had gone into improving Ernest Wright, and the amount of time and care that had gone into things like getting the windows right, re-pointing the walls in the correct way, making sure the packaging was correct, improving processes and improving the text and interpretation around the objects.”

“If other British manufacturing companies had done what Ernest Wright is doing now, many more would still be thriving.”

Craftland is a fascinating, inspiring and ultimately uplifting portrait of heritage crafts – very much endangered, but very much alive – throughout the UK. As Fox puts it:

“However far we slide into the digital ether, the materiality of making something good and holding it in our hands will never cease to draw us to it.”